Researchers have identified that hormonal changes, particularly a drop in growth hormone and increase in cortisol, are the hidden causes of visceral fat in middle age. These changes accelerate fat accumulation around the abdomen, increasing health risks such as diabetes and heart disease.

ManlyZine.com

Visceral fat in middle age isn’t just a cosmetic concern—it’s driven by hidden biological factors. Scientists now reveal that hormonal shifts, stress, and lifestyle changes are primary contributors. Understanding the hidden cause of visceral fat can help middle-aged adults implement effective strategies to reduce belly fat and protect long-term health.

Visceral fat speeds up aging and slows down metabolism, so it increases our risk of diabetes, heart problems, and other chronic diseases. Many people notice belly fat appearing almost overnight during middle age. Recent groundbreaking research explains the reason behind this change. Scientists have found that there was a unique group of stem cells that emerges as we age and actively drives belly fat accumulation.

Visceral fat differs from the fat you can pinch with your fingers. It wraps around your internal organs and makes up only a small part of your body’s fat. All the same, it plays a crucial role in various health problems. Scientists have finally revealed the surprising cause of this fat buildup. A new type of adult stem cell called CP-A appears with age and improves the body’s massive production of new fat cells, particularly around the belly. The research shows that more than 80% of this tissue’s fat cells were newly generated, not just enlarged. Scientists also found a signaling pathway called leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) that proves vital to these CP-A cells’ multiplication and evolution into fat cells.

Table of Contents

Why Belly Fat Increases in Middle Age

Your body changes in unwelcome ways during middle age. This is especially when you have to deal with where fat builds up. Young adults might see their weight spread evenly throughout their body. But people in their 40s and beyond notice their waistline expanding—even if they haven’t gained much weight.

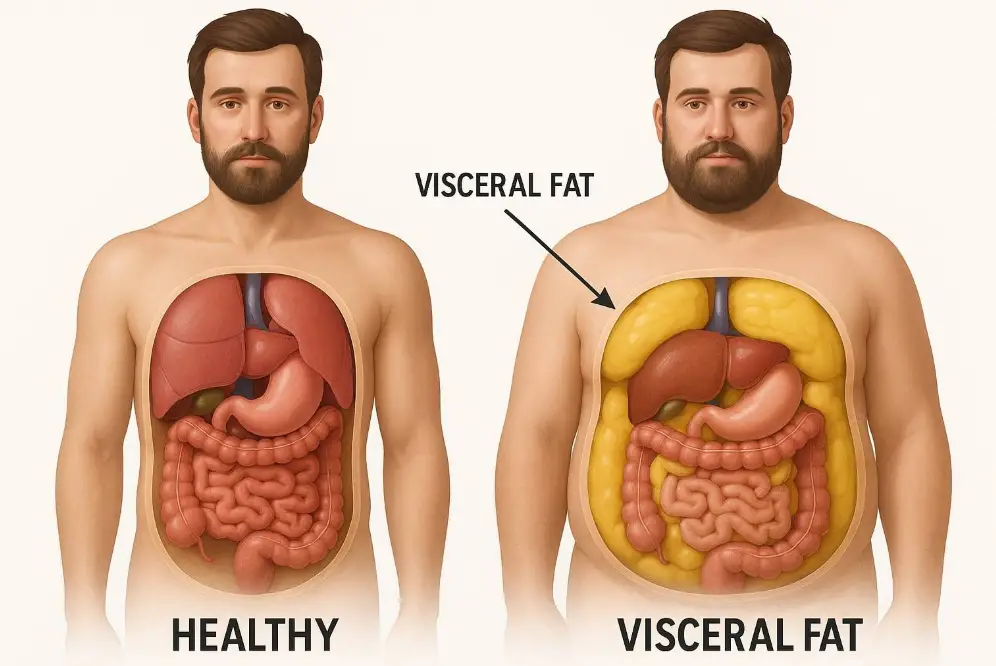

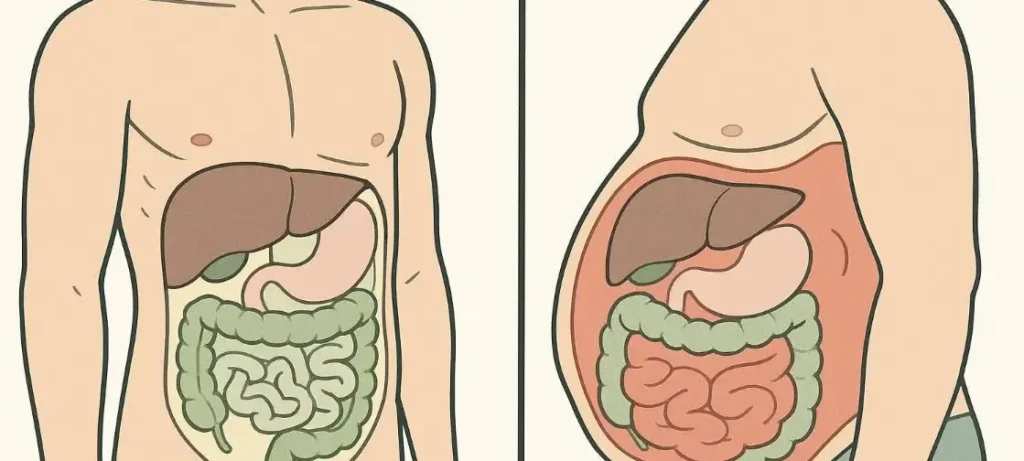

What is visceral fat and why it happens

Visceral fat builds up deep in your abdominal cavity and wraps around vital organs like your liver, intestines, and stomach. You can’t see it from the outside because it hides behind your abdominal muscles—unlike the fat you can pinch between your fingers. This fat makes up only 10% of your total body fat, but its impact on your health is substantial.

Doctors often call visceral fat “active fat” because it affects how your body works. It behaves like an endocrine organ by releasing hormones and other chemicals that can lead to serious health problems. Research shows too much visceral fat links to many health issues:

- High blood pressure and unhealthy blood lipid levels

- Type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance

- Heart disease and stroke

- Certain types of cancer

- Sleep apnea

- Fatty liver disease

- Early death from various causes

The danger comes from visceral fat’s production of proteins called cytokines that cause inflammation throughout your body. It also creates substances that lead to angiotensin, a protein that tightens blood vessels and raises blood pressure.

Visceral fat vs subcutaneous fat: key differences

Your body has two main types of fat, each with different properties and health effects:

Subcutaneous fat makes up about 90% of your total body fat and sits right under your skin. You feel this fat when you pinch your waistline, thighs, or arms. It mostly collects around your hips, buttocks, thighs, and abdomen. This fat helps regulate your body temperature, cushions tissues, and offers protection.

Visceral fat sits deep in your abdominal cavity around your internal organs. Unlike subcutaneous fat, it flows directly to your liver through portal circulation. Studies show it produces more inflammatory substances and stays more metabolically active than subcutaneous fat.

Your body shape hints at your fat distribution. People with an “apple shape” and wider waistline usually have more visceral fat. Those with a “pear shape” and larger hips and thighs tend to carry more subcutaneous fat. Women with waists over 35 inches or men over 40 inches likely have unhealthy levels of visceral fat.

How fat distribution changes with age

As you get older, fat moves around—leaving your face, arms, and legs while building up in your abdomen. This happens whatever your total weight or waist size.

Women see dramatic changes. Research shows older women have about three times more visceral fat than younger women, but only 20% more upper body subcutaneous fat. Older men have twice as much visceral fat as younger men.

Several things cause this age-related visceral fat buildup:

- Hormonal changes – Women’s estrogen drops during menopause, which affects where fat settles in the body. Men’s dropping testosterone levels contribute to visceral fat gain.

- Muscle loss – Men lose about 14 pounds of fat-free mass between 25 and 65 years old while gaining overall weight. Women lose around 13 pounds of lean tissue. Lost muscle means calories once used for muscle upkeep now turn into fat.

- Metabolic changes – Your body gets worse at burning fat as you age, particularly around your abdomen.

By their 60s, most people exceed the healthy visceral fat threshold—about 110 cm² for women and 130 cm² for men.

Scientists Discover New Stem Cells Behind Fat Growth

Scientists at City of Hope have made a breakthrough discovery about middle-age spread. They found a new type of stem cell that appears during middle age and causes stubborn belly fat many people develop in their 40s and 50s.

What are CP-As and how they form

Scientists now understand visceral fat accumulation differently thanks to these newly found cells called committed preadipocytes, age-specific (CP-As). Most stem cells become less functional with age. CP-As do the opposite – they become more active as people get older.

CP-As come from adipose progenitor cells (APCs), which are adult stem cells living in fat tissue. Scientists wanted to learn if these APCs stayed active or slowed down in older bodies. The results surprised them. These cells didn’t slow down but became better at making new fat cells.

The research team used single-cell RNA sequencing to identify this unique group of stem cells. CP-As showed remarkable abilities to multiply and turn into mature fat cells both in lab tests and living organisms. These specialized cells show up specifically during middle age and excel at multiplying into fat cells.

CP-As develop according to a specific timeline. Mouse studies showed these cells first appear around 9 months of age. They peak at 12 months and drop sharply by 18 months. This matches the typical pattern of middle-age weight gain in humans.

How aging unlocks fat-producing potential in APCs

Most stem cells lose function with age, but CP-As break this rule. Dr. Adolfo Garcia-Ocana from City of Hope explains: “While most adult stem cells’ capacity to grow wanes with age, the opposite holds true with APCs—aging unlocks these cells’ power to evolve and spread”.

The research revealed something remarkable. Middle-aged male mice had over 80% new fat cells in their visceral tissue, while young mice had very few. Middle age triggers a wave of new fat cell production instead of just making existing cells bigger.

Young mice received transplants of these middle-aged fat precursor cells. The cells kept producing fat aggressively, which proved they changed fundamentally with age. They weren’t just responding to age-related hormones or metabolism changes.

Scientists compared APC gene activity between young and older mice using single-cell RNA sequencing. APCs barely worked in young mice but became highly active in middle-aged ones. They started making new fat cells faster.

The team analyzed human fat samples from people of different ages to confirm these findings weren’t just in mice. They found similar CP-A cells in middle-aged humans. These specialized fat precursor cells increased significantly with age before dropping in later years.

This explains why losing belly fat becomes so hard after 40. The body creates new fat cells through this age-specific process, which increases storage capacity instead of filling existing cells. Understanding CP-As helps explain why belly fat becomes such a challenge with age—and might lead to solutions.

LIFR Pathway Emerges as Key Fat Production Trigger

A key molecular pathway explains the sudden appearance of visceral fat during middle age. The leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) signaling system acts as the main controller. This system decides if CP-A cells make new fat cells or stay inactive.

How LIFR signaling guides CP-A activity

LIFR works like a cellular switch that makes CP-A cells multiply and turn into mature fat cells once activated. The pathway works through a complex chain of molecular events. LIFR activation starts a series of signals that make STAT3 active. STAT3 is a protein that controls gene expression and cell development.

Research shows that LIFR activation in CP-A cells results in:

- More cell growth and multiplication

- Better ability to turn into mature fat cells

- Higher levels of genes linked to fat cell development

- More active STAT3 signaling proteins

“We discovered that the body’s fat-making process is driven by LIFR. While young mice don’t require this signal to make fat, older mice do,” explains researcher Dr. Wang. “Our research indicates that LIFR plays a crucial role in triggering CP-As to create new fat cells and expand belly fat in older mice.”

Lab studies confirm LIFR signaling’s direct effect on visceral fat buildup. Scientists blocked LIFR through drugs or genetic changes, and CP-A cells couldn’t turn into fat cells anymore. This treatment targeted age-related fat buildup without affecting normal fat metabolism.

Why this pathway is age-specific

LIFR signaling’s age-dependent nature makes it remarkable. Young mice make fat cells without needing LIFR activation. Middle-aged mice need this pathway completely. This explains the dramatic increase in visceral fat during middle age.

Scientists proved this age specificity through several tests. “Inhibition of LIFR did not affect the adipogenesis of young APCs, indicating that LIFR signaling is specifically required for CP-As.” Mice without LIFR in fat cells showed notable differences in fat distribution.

Mice with working LIFR signaling had earlier STAT3 activation than those without LIFR in fat cells. This led to less fat expansion and smaller fat cell size. These results prove LIFR’s vital role in controlling age-related fat buildup.

This finding helps us learn about changes in visceral fat patterns with age. Our bodies switch to a LIFR-dependent way of making new fat cells in middle age. This process affects the belly area most. Scientists can now look for new ways to address age-related visceral fat buildup by targeting this pathway.

Human Tissue Studies Reveal Similar Fat Patterns

Scientists found CP-A cells in mice and wanted to see if these cells caused age-related belly fat in humans too. The results matched up perfectly between species. These specialized fat-producing cells weren’t just a lab finding – they represent a basic part of how we age.

How CP-A cells were found in middle-aged human samples

Scientists analyzed human tissue samples from people of different ages using single-cell RNA sequencing. Their analysis found similar CP-A cells in human tissues, with numbers going up significantly in middle-aged people. These human CP-As showed remarkable ability to create new fat cells, just like in mice.

The tissue analysis proved these specialized cells didn’t just exist – they actively helped create visceral fat. Research showed that human CP-As have a “high capacity in creating new fat cells”. This suggests they play a vital role in age-related obesity across different species.

What this means for belly fat in older women

CP-A cells help explain why women struggle with increasing belly fat during middle age. Women’s visceral fat increases by 400% between their 20s and 60s. Men only see a 200% increase during the same time.

Women face bigger changes during menopause as dropping estrogen levels trigger a complete shift in body fat patterns. Before menopause, women store fat under the skin around hips, thighs, and buttocks. This pattern flips when estrogen drops after menopause, turning subcutaneous fat into visceral fat.

Fat buildup around internal organs creates serious health risks. Women’s visceral fat links to insulin resistance, heart disease, and certain cancers. Post-menopausal women at normal weight but with central obesity face higher death risks than those without it.

This research explains why many women see growing waistlines even with stable weight. Their bodies actively create new fat cells through CP-A activity, which changes how fat gets distributed throughout the body.

New Research Opens Door to Fat-Blocking Therapies

Scientists have found CP-A cells and the LIFR pathway that could lead to new therapies targeting stubborn belly fat. This breakthrough might change how we deal with age-related visceral fat buildup.

How to lose belly fat by targeting CP-As

A revolutionary method to reduce visceral fat involves targeting CP-A cells directly. Research shows that blocking the LIFR pathway could slow down or redirect CP-A activity. This might help reduce stubborn belly fat that builds up during middle age. Scientists are working on ways to modify these cells without affecting normal tissue renewal. Some researchers are looking at genetic factors that make people more likely to experience CP-A effects, which could help create personalized treatments.

Potential for LIFR inhibitors in obesity treatment

LIFR inhibition has become one of the most promising strategies. Studies show that blocking this signaling pathway stops CP-As from making new fat cells while leaving other metabolic processes untouched. Mouse studies revealed that blocking an enzyme called DNA-PK led to 40% less weight gain on a high-fat diet. These mice also showed better fitness levels and fewer cases of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Other enzyme inhibitors show great potential too. Pancreatic lipase (PL) inhibitors draw attention because of their structural diversity, low toxicity, and effectiveness in the intestinal tract without side effects. These compounds help obese people by reducing fatty acid absorption and improving lipid metabolism. They lower LDL while raising HDL levels.

What future clinical trials may explore

Clinical trials will likely track CP-A cells in human volunteers to see if removing or adjusting these cells helps older adults stay fit. Injectable medications have shown promising results. A completed trial showed that liraglutide reduced visceral fat by up to 11% and liver fat by up to 33% compared to placebo. The results were even better in a 12-week trial of Lactobacillus sakei OK67 (DW2010), which showed major decreases in visceral fat area compared to placebo without serious side effects.

These targeted approaches, combined with lifestyle changes, could give us better tools to fight midlife weight gain and change how we treat age-related visceral fat.

Conclusion

The groundbreaking finding about CP-A stem cells transforms our understanding of belly fat buildup during middle age. Most health professionals used to think it was just slower metabolism or hormonal changes. Research now shows a more complex system at work through these specialized fat-producing cells that show up when we hit our 40s and 50s.

Of course, this research shows why regular weight loss methods don’t work as well to reduce visceral fat after middle age. CP-A cells create new fat cells instead of just filling existing ones, so diet and exercise alone might not tackle the biological process completely. The LIFR signaling pathway could be a game-changer to develop targeted treatments against age-related fat buildup.

Women’s bodies face tough challenges with visceral fat accumulation. Their visceral fat increases by 400% between their 20s and 60s, while men see only a 200% increase. This transformation explains why many women’s body shapes change even when their weight stays the same – their bodies make new fat cells through CP-A activity.

This research’s health impact goes way beyond looks. Visceral fat leads to chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, heart disease, and many other serious health issues. Until now, treatments focused on symptoms rather than tackling the core cellular mechanisms that cause fat buildup.

The research also opens new paths for targeted therapies. LIFR inhibitors and other compounds that block CP-A activity might prevent age-related visceral fat without disrupting normal metabolism. These treatments are still being developed but offer hope to address stubborn belly fat and its health risks effectively.

The fight against middle-age spread enters new scientific territory. Scientists now have exact targets with their knowledge about CP-A cells and LIFR signaling. This better understanding of how our bodies change with age brings us closer to solutions that work with our biology instead of fighting it – finally explaining why stubborn belly fat seems to appear overnight and how we might beat it.

FAQs

What is the hidden cause of visceral fat in middle age?

The hidden cause of visceral fat in middle age is primarily hormonal changes, including reduced growth hormone and elevated cortisol, combined with lifestyle factors like poor diet and inactivity.

How can middle-aged adults reduce visceral fat effectively?

Middle-aged adults can reduce visceral fat by combining regular exercise, a balanced diet, stress management, and addressing hormonal imbalances that contribute to middle age belly fat.

Why does hormonal imbalance lead to visceral fat?

Hormonal imbalance affects fat storage by increasing cortisol and lowering growth hormone, promoting belly fat accumulation, which is a key hidden cause of visceral fat in middle age.

Can lifestyle changes reverse visceral fat in middle age?

Yes, lifestyle changes like strength training, cardio, proper sleep, and a nutrient-rich diet can reverse visceral fat accumulation caused by hidden hormonal and metabolic factors.

What are the health risks of excess visceral fat?

Excess visceral fat increases risks of diabetes, heart disease, and metabolic disorders. Addressing middle age belly fat through understanding hidden causes is crucial for long-term health.